Cage Body

If you often find yourself awake in the middle of the night wishing you weren’t alone, I know of a place you can go where you won’t be. There’s air conditioning, always turned up too high, and a television set, on mute. The vinyl chairs are arranged in a square so everyone can look at each other, and a vending machine stands off to the side. You’ll probably leave with a complicated illness of some kind and have to come straight back, but at least it doesn’t cost anything to sit in the square and look at the other people. I go often, to the sliding door under the lit-up Emergency sign. I’m always amazed at how many people are there in the middle of the night. I’m never alone. It’s where I wait for Megan.

Megan and I are regulars at the hospital the way some people are regulars at bars or coffee shops. We arrive together and split up at the triage desk—her to the doctors and nurses and me to my chair in the waiting room under the silent TV. They never make her wait very long, just wrap a paper bracelet around her wrist, tip her back and rush her down the hall. I’m never asked if I want to come; my primary job is to fill out her paperwork. I do that until I can get someone’s attention and ask where they took her this time and when I can go in. Sometimes I don’t get to go in.

It’s busy tonight; the nurse at the desk keeps shushing me and directing me to the chairs with her pen. It bothers me, and it doesn’t—Meg’s probably unconscious by now anyway. Tonight will pass like a blink for her from here on in, and I’ll take on her time along with my own, like I always do. I’ll survive an agonizing minute only to have to live it again. I feel guilty for wishing away any of my minutes, considering.

A girl with coffee-coloured hair interrupts my thoughts, poking me in the shoulder. “Is someone sitting here?” She motions to the chair beside me, the only vacant one in the room. I shake my head and let it come to rest once again in the palms of my hands, which are cold and wet with hospital sweat. This is how you sit in an emergency room if you don’t want to make conversation.

“Thanks,” she says, silently folding into the chair, legs under, arms in, hood up. Compact. Her voice is sad, and something in it causes me to glance up again. She catches me staring. “What?”

“Nothing. Sorry.” She’s rude, but she looks like she’s about 17, so I forgive her. I was 17 once; I’d hated it too.

She starts examining her fingernails, which are covered in chipped black nail polish. She frowns at them, as though they’re her problem. As though she’s come to the emergency room at 3 AM for nail polish remover. “What?”

I realize I’m staring again. “Nothing. Sorry.”

She turns her critical gaze to my face, to the hard lines in my forehead and around my mouth chiseled out by ever-present worry and too many 3 AM emergency room visits. I look haggard, and it makes me self-conscious. I used to be pretty. Like her. “Why are you here?”

“In this chair?” Does she expect me to move? I was here first.

“No. Here. In the ER. Why are you in the ER?”

For all of the nights I’ve spent here, I’ve never been asked this before. “I’m waiting for someone. You?”

“Yeah.”

“You’re waiting for someone too?”

“Yeah.” She slides her fingernail under a piece of polish and scratches it off. It makes a horrible sound. Her eyes flick over at me. “My friend broke her leg.”

“Oh.” I nod. “How’d she do that?”

Her mouth cracks open. She’s looking everywhere. I’ve stumped her. “None of your business,” she says at last.

“Emily.” A woman appears at the girl’s side. She looks tired; she’s not wearing any makeup and her hair is piled up on top of her head, held there by a large black butterfly clip. She’s holding out a hospital bracelet like it’s a stick of gum. “Put this on. I’m going to grab a coffee from the cafeteria.”

Emily’s eyes are closed.

“Emily.” The woman’s voice is ragged. She’s been yelling. She’s been awake for hours. Her face sags but her eyes flash; she’s a confusing mix of intense sadness and fierce anger, already defeated but still fighting. “Emily,” she repeats, reaching out in one swift motion, grabbing the girl’s hand and stuffing the bracelet into it. “Put,” she steadies herself, glancing at me, “this,” she catches her breath again, “on.”

Emily’s eyes don’t open. “Whatever.”

“Not whatever.” The woman presses her lips together in between every sentence, biting them hard and turning them white. “Put it on. Now.”

Emily pushes her sleeve up, scowling in my direction without looking at me, like she knows I’m watching. She’s clearly done this before; she completes the task with one hand. She thrusts her bony wrist out, displaying the paper jewelry for the woman to inspect.

Her arm is covered in lines, some of them angry and fresh and some faded to chalk-white. The woman nods, turns, and takes off down the hallway toward the cafeteria. She walks like someone who’s used to wearing high heels; she’s unsteady in her ballet flats.

I’ve never been to the cafeteria in this hospital. I’ve never been to the bathroom here either. I sometimes get hungry, and I sometimes get uncomfortable, but I don’t want to be unavailable for even a second. Some doctors urge me to walk around or even leave the building. They say Megan would wait for me. “Go out for a bit! Go grab a coffee!” they say. Their smiles are sad. She’ll be fine. She’ll know you’re not here; she won’t go without you. We’ve seen it a thousand times. They wait.

All nice thoughts, but I always want to say something snarky about how if she can’t dress herself or control the spastic flailing of her hands, if she can’t keep herself from calling out gibberish in the middle of a church service, I highly doubt she’s going to know how to keep her body from dying at an inopportune time. I want to scream these words at the doctors. I’m not angry at them; I’m angry at the situation and the doctors are the ones standing between me and it right now. The situation is a physical being, an invader from another country; it speaks a foreign language and the doctors are its interpreters, impartial middlemen relaying its messages to me from the body of my sister.

She and I were born on the same day of the same year. Our faces and hair and skin are the same. We ate all the same things growing up and played the same games and had the same friends. We had the same parents and graduated from the same high school and waitressed at the same restaurant while we worked through similar programs at the same community college.

Then one day, her body turned on her, quit working the way it always had, shut up like a steel trap with her inside it. Snap. It was like hugging someone as they were struck by lightning, having them crumble into ash in your arms. I can’t understand how I was untouched by something that big and that close. How it could claim all of her and none of me.

So now I take care of her; I carry her cage body around and poke food into it and talk to it, hoping she’s still alive in there, that my voice is soothing and comforting. Sometimes I say to her, “I’ll get you out of there, Megs,” or, “This doctor looks like he knows what he’s doing. He’ll get you out.” Sometimes her body smiles at me, but her eyes loll off into the corners of the room. Sometimes her eyes look at me but her mouth droops open and the rest of her hangs limp in her wheelchair. Maybe, I think sometimes, she escaped long ago and I’m just lugging an empty cage around.

Emily pokes me again. “Hey, sorry. Do me a favor, okay? When my mom comes back, tell her I’m in with the doctor. Tell her they’re keeping me overnight and she can go home.”

I frown. “And you’re just going to leave?”

“Well, yeah.”

“And your mother’s not going to want to say goodnight or talk to the doctor?”

Emily scoffs at this. “No.”

I gape at her. “I don’t…I don’t think you should…leave.” I expect my reaction to elicit some level of rage from her, thinking back to when I was that age and how I acted when my dad told me I couldn’t do something, but I’ve clearly overestimated her interest in my opinion. She shrugs and turns to the man reading a magazine on the other side of her, repeating her request to him. He nods and she stands up. She doesn’t even glance at the triage nurse on her way past.

I stand too. I’m not a brave person, and I’m not sure what I’ll do, but it doesn’t feel right to do nothing.

I catch up to her just outside the hospital doors, reach out my hand and jab her in the shoulder the way she’d done to me. She spins around; I can tell she’s expecting her mother. When she sees me, she relaxes. I tense. She doesn’t say anything at first, and I don’t either. Then, “What?”

“I,” I begin. I what? “I’m not going to make you go back inside or anything.”

“Okay.”

“But I think you should come anyway.”

The girl smirks. “No. I don’t think so.” She starts walking away again.

That was all I had. I can’t tackle her. Can I? I call after her. “What about your friend? With the broken leg?”

She snorts at me over her shoulder, but stops walking. “Pretty sure you’re not that stupid.” She looks me up and down with disdain and raises her chin. “Who are you, even? I don’t need another person who doesn’t care pretending like they do. If it would make you feel better, you can tell my mom you tried to stop me.”

I sputter as she walks away, knowing I should say something more but not knowing what, and then I start to cry. It surprises me because I’m not sad; I’m something else. Something that burns a little. Something like seething rage.

I’m blisteringly mad.

I’m mad at all the cages.

“What’re you trying to save her from?” The voice comes from behind me; it belongs to a grey-haired woman with a wrinkled face, hunched over a walker, dragging on a cigarette. “Dying? Is that it? You trying to save her from dying?” She looks obstinate; her tone is haughty and mocking but her mouth is lazy. Her words stick together. The sign above her left shoulder politely asks those in its vicinity not to smoke. “Everyone here is obsessed with keeping everyone else from dying. Why? Why is everyone so worried about saving each other? We’re all going to die, even them doctors. Let the ones who want to go, let them go. That’s what I say. People been trying to keep me alive since I was born. Not ‘cause they want me around, just ‘cause people are obsessed with keeping other people alive. Obsessed.” She spits this word at me. I still say nothing. She doesn’t want me to, I can see that.

Does Meg want to go?

I’ve often wondered. The doctors say it will happen soon, any day now. They’ve been saying this for years. When we’re rushing into the ER with her lips blue and her body convulsing, the only thing I can think is that I’m losing her, that I need to get her and bring her back. I always get her in on time, barely on time. The doctors save her life, what’s left of her life. I sit on her bed after it’s all over and say, “That was close, Megs. You were almost taken again.” But what’s trying to take her? Maybe she’s running away. Maybe she wants to go and I’m nothing but a glorified prison guard, on high alert, day and night, watching the door of her cage for the slightest movement, for the earliest sniff of an escape attempt.

How could I know, one way or the other? As soon as these thoughts come, I think, but maybe she’s like a baby again, just the slightest glimmer of consciousness stuffed into this big old body, and maybe the only thing she’s aware of is my existence, my love, and my earnest care for her. Maybe she’s happy in this life, like a baby’s happy when it has all the basic things. I can’t know, and it drives me crazy.

There’s a hand on my shoulder; it’s a nurse I’m familiar with, and she wants me to come with her to Meg’s room, where Meg is stable and breathing and recovering. She spends most of her time doing these things, the rest of it listening to me read her a book or push her wheelchair by the lake.

I follow the nurse to Meg’s room and sit on Meg’s bed and hold Meg’s face with both of my hands and try to see into her eyes and ask her, “You in there, Megs?” Holding the rungs of her darkened cage, calling into the corners, trying to detect movement. Are you in there? Do you want me to pick this rusty lock and let you out? Come up to the bars, here.

She doesn’t answer, but her cheeks are warm, and I imagine the twitching I feel in the facial muscles is her trying to smile. I smile back. “Megs,” I say. “You look beautiful.” She doesn’t have stress lines on her face like I do. I crawl into the hospital bed beside my sister and wrap my arms around her like a softer cage. I close my eyes and lay perfectly still. She can’t come out, but I often imagine I can go in.

I squeeze between the bars and find my sister huddled in the corner. She’s not a baby, and she’s not a prisoner. She’s just my sister. She wants to go abroad for summer vacation, she wants to become an architect and have three babies. Her favourite song is a classical piano piece called Spring and she hates asparagus. I sit down beside her and lean against her. I tell her the things I know about her. I feel her push back into me. I say, “I’m here.”

And she says, “I know.”

**

Suzy Krause is a writer from Regina, Saskatchewan, where she lives with her husband and two children. Her debut novel, Valencia & Valentine, is forthcoming from Lake Union Publishing in the summer of 2019, and she was also a contributing writer for The Magic of Motherhood, published in 2017 by HarperCollins.

**

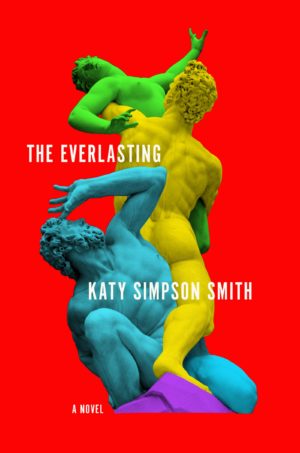

Image: Flickr / Radek Bet